by John Monroe

If you’re like me, then you probably have an internal monologue or a running internal conversation. This doesn’t mean that you’re crazy or something is wrong; most people talk to themselves. Often we ask rhetorical questions like,

“Why does my head hurt? What do I want for dinner? Why do I feel this way?”

We discuss the reality around us as we navigate our internal world.

When I finished my Master’s program and became a full-time therapist, I believed that my emotional and mental health would be in constant growth and balance since I worked in mental health. I knew the techniques, theories, appropriate questions, and coping skills. I was not prepared for the growing cloak of shame that began to weigh me down step after step, day after day.

Growing heavier as I attempted to bully myself into feeling better.

“Just breathe; you know you shouldn’t feel this way.”

“What’s wrong with me? If I can’t take care of myself, I should just quit.”

“I’m pathetic; I can’t even get rid of my own anxiety.”

These thoughts loomed over me and grew like a fire. Threatening to consume me as I collapsed into fear. As my anxiety grew, my past began to haunt me. Painful memories I had buried down could no longer be suppressed. My hurt, fear, anger, and loneliness became my own personal monster, well-equipped to remind me just how worthless I was. It took desperation before I admitted it was time to begin my own personal work again. Filled with shame, I booked my first therapy session since grad school.

I couldn’t even make it one year.

Over the coming weeks, I finally accepted that I hadn’t really healed from my past just because I knew the techniques and had done some counseling. Then I latched onto something I tell my clients all the time - it’s okay the past still hurts; you’re allowed to be human.

In all of our stories we have a childlike version of ourselves that can be treated one of two ways:

We can listen, empathize, and be present with them. Creating space to heal.

Ignore and dismiss how they feel, just like they’re used to.

Maybe you don’t relate to those two things, and that’s alright. I didn’t think I would. I had a great childhood. My parents loved me (and still do), and I had (have) great siblings. I was still emotionally neglected.

A difficult reality to live in understands that good and loving families can still emotionally fail their children.

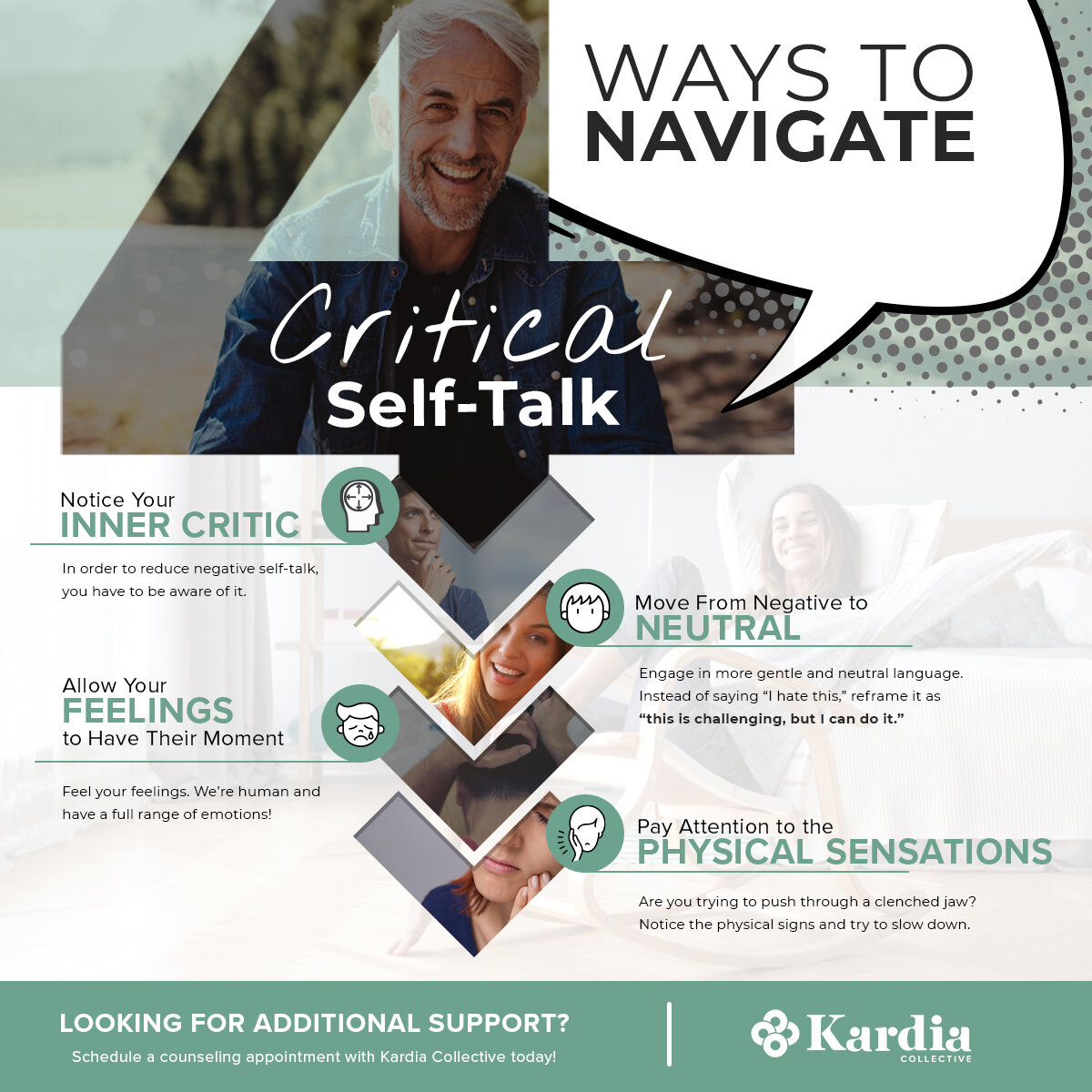

Through this, I realized I couldn’t bully myself into feeling better and it was okay to grieve the things that happened when I was a child as an adult. It was only through allowing my sadness and anger to have their moment, that I was able to weep bitterly and see that as my emotions rose and peaked, I was alive on the other side. It’s one thing to have the language to describe how we feel. It’s another thing altogether to feel them.

Giving space to feel emotions means tuning into your body and paying attention to the sensations it creates to communicate. Like when you’re driving and going through the list of things you have to get done. “Get the groceries, finish the notes, upload the video, update the client list, respond to emails, text your wife, don’t forget to pick up your son.” All while your shoulders begin to tense and your neck is hurting, but you’re pushing through.

The fear of not being enough grows.

Rather than push through, like many of us so often do, notice all that tension, see how your body is trying to tell you, “this is too much, slow down.” We notice not so that it goes away; we do it to identify what we need. The more we listen, the more we allow our bodies to move through the emotions of how God designed them.

Peter Scazzero says it best,

“To feel is to be human, to minimize or deny what we feel is a distortion of what it means to be image-bearers of God.”

I write this not as someone who has it all figured out. I write this as someone who feels free after a long time living ashamed. Again, who is remembering to make space to be human; holding onto the truth that God gave me these emotions.

He wants me to feel them and feel them with me.